Tutorial¶

This section covers basic command invocation as well as a tutorial on writing a simple script in the Python Script Provider.

Basics¶

This section explains some basic usage of DbgScript. For details see the DbgScript Reference.

Running Scripts¶

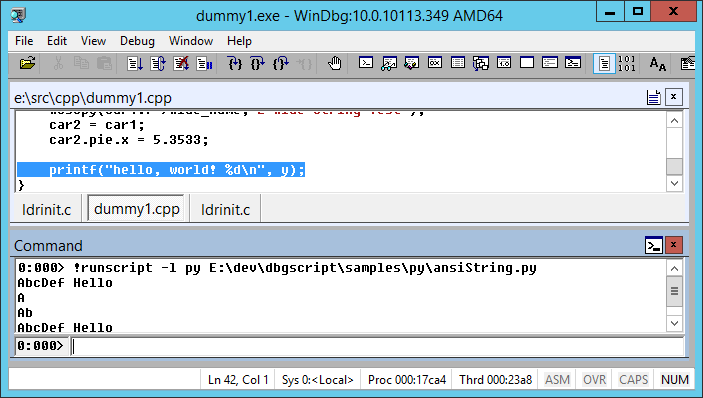

To run a script, use the !runscript entry point. For example:

!runscript -l rb E:\dev\dbgscript\samples\rb\stack_test.rb

You can use !scriptpath to shorten the path you need to pass to !runscript.

Ad-hoc Evaluation¶

!evalstring can be used to evaluate an ad-hoc statement. For example:

0:031> !evalstring -l rb puts DbgScript.get_threads

#<DbgScript::Thread:0x000045f764b788>

#<DbgScript::Thread:0x000045f764b760>

...

This example evaluates the statement puts DbgScript.get_threads in the Ruby

script provider. The output is shown in the debugger (in this case, an array

of Thread objects.)

Other Entry Points¶

!scriptpath¶

This takes a comma-separated list of paths to search when running scripts. For example:

!scriptpath e:\dev\rb_scripts,d:\pythonscripts

Note that the separator is a comma, not semicolon. Semicolon is reserved by the debugger to separate commands.

Run with no arguments to see the current path list.

Example¶

The following example demonstrates a simple program along with a sample script to introspect its contents using the Python Script Provider. The script is simple to port to other languages like Ruby or Lua.

Suppose we have a simple C++ program:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 | #define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

struct Foo

{

int a, b, c;

int arr[5];

char name[100];

wchar_t wide_name[100];

};

struct Bar

{

Foo foo;

float x, y;

};

struct Car

{

Foo* f;

Bar pie;

};

int main()

{

Foo localFoo;

Car car1, car2;

int y = 6;

car1.f = new Foo;

memset(car1.f->arr, 'a', sizeof(car1.f->arr));

car1.f->a = 6;

car1.f->b = 12;

car1.f->c = 245632;

strcpy(car1.f->name, "AbcDef Hello");

wcscpy(car1.f->wide_name, L"Wide String Test");

car2 = car1;

car2.pie.x = 5.3533;

printf("hello, world! %d\n", y);

}

|

If we run it in a debugger until the printf line (42), we can start to

inspect the various objects we’ve created and populated.

For example, we can read the string in car1.f->name in various ways:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | car = dbgscript.create_typed_object('dummy1!Car', 0x00000eb64f1fbf0)

# Read ANSI string.

#

print (car.f['name'].read_string())

print (car.f['name'].read_string(1))

print (car.f['name'].read_string(2))

print (car.f['name'].read_string(-1))

#print (car.f['name'].read_string(100000)) # error: count too large.

#print (car.f['name'].read_string(0)) # error: count must be positive.

|

This example showcases dbgscript.create_typed_object() to create a

dbgscript.TypedObject from an address and type directly. This is a

common way of bootstrapping a script (though normally, the address would be

passed as a command-line argument to the script.) If the root object is a global,

it may be obtained with dbgscript.get_global().

This example also shows field lookup using the explicit obj['field'] syntax.

Fields may also be looked up though dynamic property syntax, i.e.

obj.field. In this case though, the explicit syntax must be used because

the field being looked up has the same name as, and thus would be otherwise

hidden by the built-in property dbgscript.TypedObject.name. Built-in

properties/methods take precedence.

Lastly, we read the string from the TypedObject wrapping the name field

with dbgscript.TypedObject.read_string(). This yields a Python str

ready to be printed out as usual.

Notice that stdout is redirected to the debugger’s command window, as expected.